Working with GitHub

From earlier:

Git is a tool to control revisions. GitHub is a web service centered on git. It provides repository hosting as well as a suite of workflows to aid collaboration.

In this section you will learn about remote repositories, which are histories that are not next to your working directory. The operations involved in using these include pushing, pulling, forking, and pull requests.

Mini-exercise: pushing your project back to GitHub

You started out creating a project on GitHub, which you cloned to your own computer. All the changes you recorded since then are stored locally, on your computer. You need to explicitly tell git that you want to push the changes back to GitHub.

To understand how to do this, you need to keep in mind that git is distributed: every copy of your data contains the entire history. There is nothing special about your local copy vs GitHub’s copy vs the copy on your department’s computing servers. Therefore, you have to deal with “remotes”, which are your local git’s address book of other copies of the history. Check it out:

$ git remote

origin

Git is saying that it knows about a single remote repository, called

origin. To see what it knows about this remote, use the -v (verbose)

flag:

$ git remote -v

origin git@github.com:jni/pycalc (fetch)

origin git@github.com:jni/pycalc (push)

That tells both the name of the remote, and its location. “origin” is the default name for the remote from which you cloned the current repository.

Think of the output like an address book for the repo: the names on the left, and the addresses on the right.

Now, push your local changes back to the origin:

$ git push origin master:master

Counting objects: 36, done.

Delta compression using up to 4 threads.

Compressing objects: 100% (36/36), done.

Writing objects: 100% (36/36), 3.33 KiB | 0 bytes/s, done.

Total 36 (delta 25), reused 0 (delta 0)

To git@github.com:jni/pycalc

8ab0457..8de6fb7 master -> master

Read the above as “push to “origin” my branch “master” onto its branch “master”. Branches are managed locally for each repository, so the branch names don’t actually have to match. That is, we could easily have written:

$ git push origin master:other-branch-name

and then the contents of our branch master locally would be mirrored in the

remote branch other-branch-name on origin. In order to tell git to keep

track of matching branch names, use the option --set-upstream:

$ git push origin --set-upstream master

This tells git: “push master onto origin’s master, and note that they are

mirrors of each other.” This means that later, we only need to do:

$ git push origin

And git will know that master goes onto origin’s master.

After this, you’ll be able to refresh your page on GitHub and browse your code’s history.

Exercise 4: GitHub pull requests

For this exercise you will have to pair up with your neighbour, which we will name Alice. (And your name is Bob, in keeping with the computer science literature.) Decide now who will be Bob and who will be Alice in the pair.

As Bob, you should delete your “pycalc” repository on GitHub (this is done under “Settings” in the right-hand menu). You’ve realised that Alice has her own version and that you can both save effort by collaborating on this project.

You’ve been wanting to do some arithmetic on some data, but the first

number you need to add is often a decimal number. In those cases, the

compute function falls short. (How?)

You want to modify it so that the first number is allowed to be a decimal number.

Navigate to Alice’s repository on GitHub (https://github.com/[Alice’s username]/pycalc), and click the “Fork” button. This will create a copy of Alice’s repo on your GitHub account, which you can then clone on your machine as before. But note that you need to delete your existing work, or git will complain! Instructions below (some of the directories and obviously the “bob” username needs to be changed to yours!):

$ pwd

/Users/bob/projects/pycalc

$ cd ..

$ rm -rf pycalc

$ git clone git@github.com:alice/pycalc

$ cd pycalc

$ git switch --create decimals

Edit the calc.py file so that num0 is converted with float

instead of int. (Leave num1 unchanged for now.)

Now commit those changes and push them to a new branch on GitHub. If you use

the --set-upstream flag, you tell git to create a branch with the same

name that “tracks” the current branch. This makes future pushes easier.

$ git add calc.py

$ git commit -m "Allow num0 to be any decimal number"

$ git push origin --set-upstream decimals

Go to the GitHub page for the project. You should see a new button showing that you’ve recently updated a branch and prompting you to initiate a pull request. (You can also copy the “new pull request” address from git’s message when you push.)

Here’s how this works: you don’t know Alice. You probably have never met her. So it’s natural that you can’t just push random stuff willy-nilly to her repository. However, you do have a shared history, because you forked hers, and she has access to your new changes. So, instead of pushing your changes, you ask her to pull from your own history.

The PR will tell Alice that you’ve made some changes to the code and you would like her to incorporate them into her project. Notice that you did this without needing any special access from Alice! This is the magic of GitHub and open source.

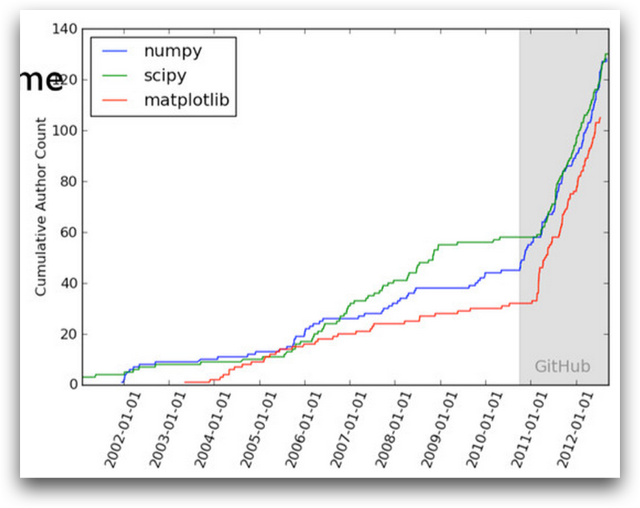

Check out the impact that GitHub has had on a few open source Python projects:

Click on the PR button and fill in the form. Filling in a useful title and message here is very important!

Pull request etiquette

Make sure your title and description are informative. 99% of the time, when you make a pull request (PR), the person on the other end is very busy, knows no background about the PR and doesn’t understand why you made the changes you made. In general, the onus is on the requester to comply with all the repository’s formatting guidelines and so forth. By convention, many repositories have a

CONTRIBUTING.txtfile explaining the contribution process. If it’s there, be sure to read it before submitting a PR!When in Rome, do as the Romans do. Look at their existing codebase and try to follow their example. (This is not to say that you can’t improve on it; but make sure your documentation and testing at least meets their standards.

Alice should get an email notification that there is a pull request to her project. Clicking on it, she will be taken to the web form for the PR, where she can examine the changes that Bob has made (the “Files” tab).

Alice will note that this great change would be made much more useful if it

also used float for num1! She comments on the

PR page: “This is a great addition, thanks! Could you please do the same for

num1?”

On his machine, Bob makes the requested change, commits, and pushes his changes:

$ # ... edit calc.py ...

$ git add calc.py

$ git commit -m "Use float for num1's conversion also"

$ git push # no need to specify repo or branch anymore, having `set-upstream`

If either Bob or Alice go back to the PR page, they will see that the PR has been automagically updated with Bob’s new changes! (Though they may need to refresh the page.)

Alice, satisfied with the update, can now click on the “Merge pull request” button and incorporate Bob’s changes to her code!

One last thing needs to happen to really synchronise everyone’s histories.

Although Alice has Bob’s changes, Bob doesn’t have Alice’s commit

incorporating his changes. If he continues to work on his decimals branch,

their histories will diverge. And if he works on his master branch, his

changes won’t be there!

The solution is for him to pull the master branch from Alice’s repository. For this, he needs to add it to his list of remotes (remember remotes?):

$ git remote -v

origin git@github.com:bob/pycalc (fetch)

origin git@github.com:bob/pycalc (push)

$ git remote add upstream git@github.com:alice/pycalc

$ git remote -v

origin git@github.com:bob/pycalc (fetch)

origin git@github.com:bob/pycalc (push)

upstream git@github.com:alice/pycalc (fetch)

upstream git@github.com:alice/pycalc (push)

$ git switch master

$ git pull upstream master # get upstream's master branch, and merge

$ git push origin master

Bob can now inspect his history log and see that both his changes and Alice’s

merge are there. Use GitKraken/GitX/GitTower/other GUI for this, or the lsd

alias we learned earlier, or a simple git-log will also do.

Bonus exercise 1: self-PRs and code review

Do the reverse approach, which is a bit different. Alice has gained a

collaborator in Bob. Even though she still maintains control of the project

repository, she wants to enlist his help. She creates a branch, adds a line or

two (for example, she might want to add a test function, test_compute, that

runs compute for a few known values and makes sure the results match up), then

creates a PR against her own repository. She then asks Bob to review her

change by mentioning his username (e.g. @bob, as in Twitter) in a comment on

the PR page. Only when Bob gives his ok (or perhaps he spots a typo) does she

merge.

This practice of requesting code reviews for pull requests, even when you control the repository, is universal among programming teams, because it dramatically improves the quality of the code. Two pairs of eyes are more than twice as effective as one pair.

Bonus exercise 2: rebasing

Bob thinks testing is a swell idea, and adds a test function at the bottom in

a branch called test-2, and makes a PR.

Meanwhile, Alice herself has also been busy and adds a third test function at the bottom of the same file, before merging Bob’s PR.

Bob’s pull request now shows a greyed out “Merge” button, because there are merge conflicts! Unlike before, you don’t have access to the history on GitHub, so you can’t just proceed with the merge and fix the merge conflicts.

The common solution is to rebase, that is, to replay the changes on Bob’s

branch on top of the latest master from Alice’s repository.

$ git switch master

$ git pull upstream master

$ git rebase master test-2

During the rebase, Bob will have merge conflicts. He needs to fix these as

before, git add the file, and then git rebase --continue to complete the

rebase.

Finally, Bob will try to push back to his GitHub account but this will fail.

(Why?) The solution is to use git push --force-with-lease.

Notes on why you should make your own code open source

- The idea that you will be scooped by someone looking at your code is ludicrous. Reading code is hard work and no one will do it on the off chance that there is a Nature paper buried in there.

- Your own coding habits and practice will improve just by knowing that it’s out there. (Shame is a powerful motivator! =P)

- If someone does look at your code and finds it useful, chances are that you will have gained a new collaborator, not a competitor.

- It is just good scientific practice!

- See my blog post Why scientists should code in the open and Jake Vanderplas’s presentation In defense of extreme openness.